Share

Tell other teachers, parents, and students about us.

Follow

About

Explore an iconic setting of Texas history with an immersive journey through video, 3D virtual environments, photos, and documents of the Presidio La Bahia, also known as Fort Defiance, as well as Fannin Battleground State Historic Site in and around Goliad, TX.

Virtual Walk-through

Presidio La Bahia Museum

Interior walk-though of the museum located on the west side of Presidio La Bahia.

Presidio La Bahia Barracks

Interior walk-though of the barracks located on the south side of Presidio La Bahia.

Presidio La Bahia Chapel Interior

Interior walk-though of the chapel located on the north-west corner of Presidio La Bahia.

Map

The following map will help you get oriented on this field trip. If you allow your browser to know your location (and your OS permissions allow it), we’ll plot your location to show your students their proximity to the places discussed on this page.

Additional Media

Photos in the Portal to Texas History

Note the condition of the walls, roof, and exterior of Presidio La Bahia.

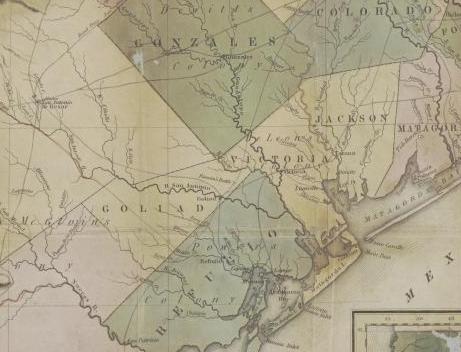

Maps & Aerial Photography

1839 Map including Goliad, Victoria, and an X where “Fannin’s Battle” took place, overhead drawings of “Fort Defiance”, showing the positions of artillery, fortifications, barracks, and other notable points, and modern aerial photos of the area.

Battle of Coleto Creek

Drawing of Fannin’s Fight, showing the Texas Infantry, breastworks, and lines of assault by Mexican Dragoons and Infantry. Aerial view of the surrounding area, now the Fannin Battleground State Historic Site, and the cotton gin screw that marks the location of the fight.

Archival Video of Restoration

Linked below is 3 minute clip of archival footage that aired on WBAP-TV (Fort Worth, TX) on November 29, 1964. It shows the state of the Presidio in the 1960s during archeological work and restoration. There is no sound in the original media, but a script is available to read on The Portal to Texas History.

Chronology of Events

- February 5, 1836

- The Texas army’s supplies (like food, clothing, and ammunition) were supposed to reach Goliad but got delayed because a ship carrying them wrecked.

- February 8, 1836

- James Fannin sent a letter to the provisional Texas government stating his plans to gather troops in Goliad at Presidio La Bahia.

- February 12, 1836

- Fannin took his troops to Presidio La Bahia and started making it stronger, calling it “Fort Defiance.” This location was important for supplies and protecting the coast.

- February 13, 1836

- Fannin received orders from the Texas government to protect important areas, like Refugio and Gonzales, and to defend Goliad.

- February 16, 1836

- General Jose de Urrea entered Texas with Santa Anna’s armies and begins marching toward Goliad.

- February 25-26, 1836

- William Barret Travis, the commander of the Alamo, asks Fannin for help and reinforcements because the Alamo has been surrounded by Santa Anna’s army. Fannin starts marching toward San Antonio on February 26th but has to turn back because of broken wagons and few supplies.

- February 28, 1836

- Fannin thinks about abandoning Fort Defiance (Presidio La Bahia) because they lack supplies. But the government doesn’t know about their supply problems and orders them to stay in Goliad. People under Fannin start to doubt his leadership.

- March 2, 1836

- During his advance toward Goliad, General Urrea surprises and defeats a small force of Texans at Agua Dulce Creek. Almost all the Texans in the fight are killed or captured, except five survivors who join Fannin in Goliad. This battle took place about 60 miles from Goliad.

- March 6, 1836

- The Alamo is defeated by Santa Anna’s army, and everyone inside is killed. Mexican forces start moving further into Texas.

- March 9, 1836

- Captain B. H. Duval writes a letter describing the situation in Goliad. He says Fannin is not liked by many volunteers, and they’re only staying together because they know they’ll have to fight soon.

- March 10-11, 1836

- Wagons sent for supplies return with very little food and resources. The soldiers in Goliad are getting ready for an attack, but they’re running out of food and other essentials.

- March 11, 1836

- Houston learns about the fall of the Alamo on March 6th and sends orders to Fannin. Houston tells Fannin to retreat to nearby Victoria as soon as possible, taking his troops and some cannons with him. Fannin is also supposed to destroy Fort Defiance and help defend and evacuate Victoria before sending a part of his force to Gonzales to join Houston’s army.

- March 12-15, 1836

- There’s a battle at Refugio as troops sent by Fannin to help evacuate the town are attacked and defeated by General Urrea’s army. Many are captured, and Urrea’s forces learn about Fannin’s plans.

- March 13-14, 1836

- Fannin gets orders from Houston to retreat to Victoria, but he’s worried about the fate of troops that he sent earlier to Refugio. So Fannin delays his retreat.

- March 14-16, 1836

- Fannin sends messengers to find out what happened to the troops sent to Refugio, but they don’t return, causing anxiety.

- March 16, 1836

- Mexican forces execute Texas prisoners at Refugio.

- March 17, 1836

- Fannin learns about the defeat of the Texans at Refugio and decides to begin his retreat soon.

- March 18, 1836

- Fannin spends the day preparing his men for their retreat.

- March 19, 1836

- Fannin’s troops finally begin their retreating from Goliad but face difficulties like heavy fog, broken carts, and losing their largest cannon in the San Antonio River. They stop to rest in an open prairie, when General Urrea’s forces find and surround them.

- March 19-20, 1836

- Battle of Coleto Creek: Fannin’s troops are surrounded by the Mexican army in an open field. They lack experience and supplies. Many are hungry and thirsty. They think about escaping during the night but decide against it because that would mean they would have to leave wounded men behind. When Urrea’s troops bring in heavy cannons, the Texans surrender after taking heavy losses, with about 70 killed or wounded out of 275 men.

- March 21, 1836

- Mexican forces capture the town of Victoria.

- March 22, 1836

- Another force of Texans under William Ward are surrounded by Mexican cavalry and forced to surrender. Roughly 85 men, along with Ward, are taken back to Goliad and imprisoned in a church with other Texan prisoners on March 25th.

- March 20-25, 1836

- Texan prisoners are brought back to Presidio La Bahia. It takes three days to bring all the Texan wounded to Goliad from the battlefield. Fannin arrives in Goliad on March 22nd. General Urrea receives an order from Santa Anna to execute all the prisoners, and the last Texan prisoners arrive in Goliad on March 25th.

- March 26, 1836

- According to Jack Shackelford’s diary, the Texian prisoners believe they will be released to the United States, including Fannin. They are in good spirits and even play and sing a tune, “Home, Sweet Home.”

- Goliad Massacre - March 27, 1836

- On Palm Sunday, Texan prisoners were marched out of the Presidio La Bahia in three groups. They believed they were being paroled or released, but it was a deception.

- The Mexican troops, under the command of Col. Jose Nicolas de la Portilla and following orders from Santa Anna, suddenly turned and fired on the Texan prisoners.

- This resulted in the execution of roughly 400 Texian prisoners. Fannin was shot later by Santa Anna’s troops.

- A few Texians escaped into the woods and eventually made their way back east, some of them joining Sam Houston’s army.

All Viewing Options

Rights

Support

Learn about our team, supporters, and how to contribute or give back.